‘The Big Scrub’, Northern New South Wales, Australia

The Big Scrub is located in Northern New South Wales, Australia. This vast area of subtropical rainforest was cleared by European settlers from the 1840s, firstly for its valuable cabinet timber species, in particular red cedar, and later for agricultural selection, primarily dairying and agriculture.

This region is of special significance to me, as my Great-grandparents were some of the first pioneers to select and clear this land along the Coopers Creek, a perennial stream of the Richmond River Big Scrub, later to be called the township of Eureka.

Early Exploration of The Big Scrub and ‘Red Gold’

In 1842, the original cedar cutters were attracted to the area by the the enormous stands of ‘Red Gold,’ or Red Cedar trees that stood dense and tall on the river banks.

Red cedar was one of the first export products for the fledgling settlements of convict NSW. Cedar exports continued to rise, coming third in significance to wheat and wool, during the 19th Century. Being a slow-growing tree, the Red Cedar produces beautiful soft timber that was used for furniture and, (wastefully), flooring, in Australian housing. The abundance was greater than anyone had experienced before and the quality of the timber was exceptional so more and more settlers and cedar cutters flocked to the district. Before long, all the cedar had been logged out.

Selection of the Big Scrub and Land Clearing

As a condition of receiving land grants, the selectors had to clear all the vegetation. Not the 15 per cent along the streams or anything like that, “clear it all,” they were told.

http://www.abc.net.au

Settlement of the Big Scrub had commenced in the areas around Alstonville, by 1865 under the Conditional Purchase provisions of the Robertson Land Act of 1862. The Act meant clearing was compulsory in order to maintain your ownership of the land.

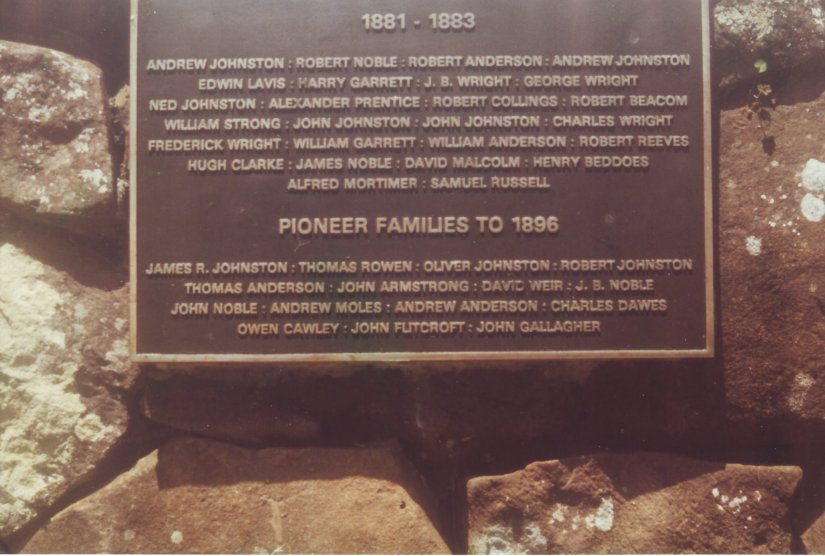

Great Grandfather, Samuel Russell, would have had to clear-fell several acres of land each year or forfeit his claim to the land. In addition, each selector had to build a house and make other “improvements” to maintain his title. This was how the Government would encourage settlement of particular areas, and by so doing, displace Aboriginal people and many animal and plant species.

The demand for good grazing land fed a steady flow of settlers into the region. Even as late as 1908 at Jiggi Creek, just north of Lismore, clearing a site for a hut was still a major undertaking; clearing an entire selection would involve months of back-breaking effort for the settler and any of his children able to help.

The Forest Disappears

This Government clearing and settlement initiative was responsible for 99 per cent of the Big Scrub being cleared. 99 % of the original forest has gone. Remnants of, ‘The Big Scrub,’ remain in National park and State Conservation areas, but most of it was burnt by early pioneers as they considered it useless to farming. The botanical diversity was not seen as valuable as it was, “just scrub”.

It is hard to be critical of early cedar cutters and settlers who contributed to this destruction; the evidence of their hardiness and enterprise, their spirit and their willingness to endure harsh conditions and to pull together is too great not to feel some admiration, notwithstanding various incidents of cruelty and worse towards the Bundjalung and other Aboriginal peoples of the region.

www.paperbarktours.com.au/StorylinesRainforestsBigScrub.html

Environmental Significance of the Big Scrub

Now only small scattered remnants of the original rainforest remain, many of them less than five hectares in area and covering less than 700 hectares in total – less than 1 per cent of the original area.

One man and his brother were able to shoot 102 wompoo pigeons now extremely rare and potentially extinct, from one white cedar in one morning and, on another day, filled two chaff bags with topknot pigeons and four brush turkeys; brown pigeons were too small to waste the powder on but, on the way home, one casually thrown stick killed six of them. These birds were destined for salting down as the family’s food. At the same time, previously uncommon cockatoos, parrots and lorikeets descended on the pioneer settlers’ crops “in clouds”. Pademelons, [a type of small kangaroo], proliferated and became a scourge to crops and pastures; bandicoots were more numerous than ever before and the brush possum appeared in numbers, driven out from the cleared forest areas. The abundance was short-lived and the forest habitat was replaced by dairy cows. Today, there are few remaining native mammals and dairy farms have largely been replaced by macadamia nut and tropical fruit plantations.

Inroads into the wildlife were heavy but in the long term may have had less drastic permanent effects on animal populations, had suitable reserves been created and maintained. But as axes rang through the forest, trees crashed and the smoke drifted through the canopy, wildlife had no hope; its habitat was almost totally erased.

http://www.abc.net.au/news

Despite the loss of such rich sub-tropical rainforest, the remnant areas remain important for migratory birds and bats, who disperse seeds of a number of species on their movement northwards. The remnant forest provides important stepping stones for birds and bats which seasonally migrate between the forests of the coast to the south. As the birds and bats are the major vehicle for dispersing seeds far and wide, the remnants are important genetic pools for seed diversity in north-eastern New South Wales.

Some early property owners preserved small parcels of their less accessible ‘upper country,’ out of appreciation of the forest’s natural values. Other patches were deliberately retained as firebreaks, (although rainforest is susceptible to fire and does not regrow from it as does eucalypt forest).

The main remnants of the Big Scrub today include Uralba Nature Reserve, Booyong Recreation Reserve, Andrew Johnston Big Scrub, Victoria Park, Davis Scrub, Hayters Hill, Boatharbour, Minyon Falls Nature Reserve, Big Scrub Flora Reserve and Wilson Nature Reserve. The only sizeable areas left are in the northeast of the state, in the Border Ranges.

Pioneer Families in the Richmond River District

Great grandfather, Samuel Russell and his wife, Sarah, were Pioneers selectors of the Eureka and Coopers Creek area, a tributary of the Richmond River. My Grandfather was born at the family farm along with about nine other sisters and brothers.

Samuel Russell, my Great Grandfather, died prematurely, of heart disease, and one could imagine the physical toll of heavy work such as clearing the thick rainforest may have contributed to his early demise. Sarah remarried and left the district. The children were spread out amongst older family members. My Grandfather moving to Wondai, to live with his sister, Annie Sheather.

The School in Eureka

Clunes Cemetery where Sarah is buried

It is difficult to locate the original Russell selection now, as boundaries and access roads have altered over time, but the area remains primarily agricultural grazing land.

It makes for a wonderful place for a day trip from Lismore or further north and makes one ponder about what it was like in the early days.

It’s very interesting for me that you still have the pictures of your dear great-grandfather Samuel and great-grandma Sarah. And that you know what your ancestors used to do. I have no idea about mine. This was a fascinating read for me, and making want to call my parents to ask what their parents used to do during those days. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Family history isn’t for everyone, but I do like to find out what their lives were like, the social history and so on. As this area is close to me and one that I used to visit very frequently when I was younger, I find it equally fascinating. The environmental loss can not be understated however and to think my own ancestor played a part in that destruction is sad. I have Danish ancestors for the main part, and have visited a house my 7th Great Grandfather built in 1801. That was very special and astonishing! They lived lives so different to our own, and yet where it not for their decisions, we could not be here.

Do you know what area your family originated from?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ah no wonder you like Scandinavia 🙂 I have not been to Denmark and the farthest up I’ve been was in northern Germany – in Kiel. My hubby and his classmates once drove to Copenhagen from Kiel. Ah my parents are both from the Philippines. But my hubby and are kids have made Singapore our home for the past 2 decades 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Singapore is in my corner of the world then. Have you lived there all your life? A drive from Kiel to Copenhagen would be fun. I have driven from Lubeck up to Denmark. I so enjoyed it. There are so many interesting towns along the way. And there is the Dannevirke to see too.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh I moved to Singapore only 20 years ago. And it was a great move. It’s easier to travel from Singapore to other parts of the world than if from the Philippines. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Absolutely – Singapore is a great hub to access Europe.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very interesting read Amanda! I didn’t know that Australia had the same big cedars that Canada had. The story of clearing the forests sound similar. Do you know which part of Europe your ancestors hailed from originally? Because of your love of Nordic things I always assumed you were a ‘new’ Aussie 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am a new Aussie, Sandy. Most perceptive of you. This part of the family, is the English sidewho came from Wells, in Somerset. The town where that comedy film, Hot Fuzz was filmed (fun fact). The remainder of the family hailed from Prussia and Scandinavia. I believe they immigrated when the enclosure laws restricted their gardening/farming practices.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting. Its good that you have all or at least some, of your ancestry records.

LikeLiked by 1 person

One side we suspect but don’t know anything about – the mystery branch!!

LikeLike

Very fascinating: the heritage/genealogy and also, sadly, the loss of biodiversity (the same thing happened all around the world: they didn’t know better, so I’m not blaming them. I actually just listened to a biodiversity webinar at work where a researcher remarked that he found it amazing how human’s are not evolutionally hardwired to preserve our Earth, but that’s it’s something we have to learn.) Anyway, that graveyard picturw along with talk of the pioneer seemed very striking to me: there they lay now, those pioneers. So many graveyards full of people whose acheivements we have no idea of.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s a very interesting point about humans not being hardwired to naturally protect our environment upon which we depend i.e. Biodiversity. I feel that stems from certain religious teachings where we are given wholesale right to have dominion over everything in the Garden of Eden maybe that has changed our attitude towards the Earth. Religious promises of an afterlife that satisfies all our desires and offers peace and contentment has perhaps allowed humans to disregard a more nurturing attitude towards nature. Whilst religion has helped folks cope with painful or difficult living conditions, our lives are so short that we tend to think more about shirt term gains whilst we are alive. This also means the majority don’t have to care so much about preserving the future on this planet for generations who come after us. Life is transient, and only relevant for our time. Unless you do something globally significant your life and achievements are quickly forgotten with the oassafe of time. Even for those who do something globally significant and might have a statue erected in their honour- those statues may be pulled down by and our being pulled down by subsequent generation who see them as irrelevant or un-pc or insulting, in some way. Why do we even want to be remembered long after we’re gone? What’s the impetus for that? To cheat death, somehow – is that why? Our legacy is often the result and consequences of all our actions and interactions in our life. Isn’t that enough for us? That’s something I might think a bit more about.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting point, the impact of religion, you are definitely on to something, I agree. Though you would think they would at least be thinking of their children and grandchildren, right?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I do wish they would !

LikeLiked by 1 person